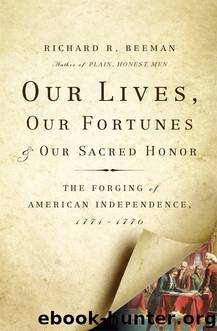

Our Lives, Our Fortunes and Our Sacred Honor by Richard R. Beeman

Author:Richard R. Beeman [Beeman, Richard R.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780465037827

Publisher: Basic Books

The Two Newcomers: Franklin and Jefferson

Though Benjamin Franklin had just returned to Philadelphia, he was well known personally by many, and by reputation to everyone there. By that time in his life, in his seventieth year, Franklin had already achieved international acclaim as a scientist and widespread respect in America as a shrewd and effective lobbyist for the colonies’ interests in London. And virtually everyone in the Congress, upon their first encounter with him, would be bowled over by his charm and his sense of humor.

Franklin had spent more than a decade in London as a colonial agent representing Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia and, eventually, Massachusetts. He had loved his time in London, and, indeed, at that stage in his life may have considered himself as much a Londoner as a Pennsylvanian. He enjoyed the high life of London politics and took pride in his close relationship with some of the most important royal officials in the empire. But as we have seen, in the wake of the Boston Tea Party and the scandal involving the publication of the letters from Massachusetts Governor Thomas Hutchinson, Franklin’s relationship with royal officials, and, indeed, his very identity as an Englishman, underwent a dramatic transformation. His confrontation with Lord Wedderburn in the cockpit in late January of 1774 would change the course of Franklin’s life, and, in some senses, the course of American history. Franklin would remain in London for more than a year after his confrontation with Wedderburn, and, in spite of his humiliation that day, he would continue in his efforts to persuade British officials to relax their coercive policies up until the final hours before his departure back home to America.6

Franklin was elected to a seat in the Continental Congress on May 6, 1775, one day after he got back to Philadelphia, and, simply by an accident of timing, he was able to be present when the Congress began its business on May 10. For the most part, he remained uncharacteristically silent during the first few months of the Congress’s deliberations. Silas Deane, writing to his wife, observed that “Docr. Franklin is with Us, but he is not a Speaker.” Deane went on to note that though Franklin had added his approval to all of the measures adopted by the Congress, he had hoped for more from the illustrious American scientist and diplomat: “Times like these,” Deane noted, “call up Genius,” and thus far Franklin, so well-known for his genius, had remained largely passive. John Adams observed the same passivity, telling Abigail that thus far “he has had but little share farther than to cooperate and assist.”7

Franklin’s outward demeanor notwithstanding, John Adams, at least in his early interactions with the most famous man in America, praised the good doctor for his support of even “our boldest Measures.” Indeed, Adams believed that, should the Americans be “driven to the disagreeable Necessity of assuming a total Independency,” Franklin would support the decision. Even at this early stage though, Adams could not resist

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19085)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12190)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8909)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6885)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6279)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5801)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5751)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5507)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5442)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5087)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4960)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4924)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4788)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4752)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4717)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4507)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)